Deep Time Materials: Concrete

Along the West Shore sit the remains of World War I and II defensive structures. Built as artillery and searchlight emplacements, now they are places to shelter out of the wind and rain. If the bottles appearing there are anything to go by, they are places to pass a drink around while looking out over the sea. As historic sites, they stand testament to a time when concrete played a key strategic role securing the natural harbour of Scapa Flow as the Royal Navy’s principal naval base.

Along the West Shore sit the remains of World War I and II defensive structures. Built as artillery and searchlight emplacements, now they are places to shelter out of the wind and rain. If the bottles appearing there are anything to go by, they are places to pass a drink around while looking out over the sea. As historic sites, they stand testament to a time when concrete played a key strategic role securing the natural harbour of Scapa Flow as the Royal Navy’s principal naval base.

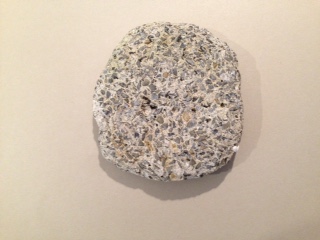

Earlier histories are visible within this concrete, too. On our Festival of Deep Time walk along the West Shore, Andy Hollinrake, archaeologist and caretaker of the Ness Battery, shows us pink colouration within the concrete, indicating the aggregate used contained granite from the basement rock which underlay Orkney prior to the deposition of the Old Red Sandstone (and thus considerably older than 416 million years). Concrete is part of the geological sequence here, but such a sequence is never purely linear; it reaches back into itself for materials and disrupts itself with discontinuities.

The presence of concrete on the shore today can appear stark. Amidst the sandstone, it sticks out like a sore thumb, an obvious and disproportionate mark of very recent human presence superimposed on millions of years of gradually accumulating geological history. Yet, crucially, it is within this geology; part of it, not alien to it. Indeed, as Andy also explains to us, during wartime, stone was scattered on the roofs of the emplacements to break up the shape and allow them to blend into the coastline from above; making their human-made identity as military structures less obvious made them less vulnerable to enemy bombing.

Searchlight emplacement on Stromness’ West Shore, photo by Carina Fearnley

Today, the role of concrete in defending Orkney is as vital as ever. The action of the sea is constantly reshaping and reducing the islands, a continuous gnawing eroding the glacial till and the underlying sandstone. As Orkney finds itself reduced year on year, the coastal built environment finds itself threatened. A particular source of concern is the loss of sites Orkney’s unique Neolithic, Iron Age, and Viking heritage, a problem believed to be exacerbated by climate change, and documented in Julie Gibson’s book Rising Tides: the loss of coastal heritage in Orkney. It is here that concrete acts as Orkney’s protector.

To take a particularly famous example: Skara Brae, Europe’s most complete Neolithic village, occupied from around 3180 BC to 2500 BC, was only revealed to modern Orkney after a storm in 1850 battered the west coast of the Orkney mainland and stripped the grass off the land. Now a concrete wall holds back the sea in an attempt to stop it taking away what it uncovered, while the land is eaten away at each end of the defences. Here, as in so many locations around Orkney, concrete buys time, holding the line for a little while at least.

As with the attempt to disguise the wartime concrete defences, it’s interesting to note the ways in which people have tried to make the manmade strata of sea defences less obtrusive. A particularly striking example of this geological fakery can be found at the Brough of Birsay. Now a small tidal island severed from the mainland over a thousand years ago by the forces of coastal erosion, today concrete defends the heritage site, but tries to do so without drawing too much attention to itself: patterning on the defences mimics the strata of the sandstone.

Defences at the Brough of Birsay, photo by Carina Fearnley

Back on the West Shore, concrete defences punctuate the coastline. From one perspective, they seem to interrupt the geology of the shore. The laminations of the sandstone, records of accretion over millions and years, seem to stop and start as the concrete interjects. Concrete’s presence in the calendar of time revealed by the stratigraphy of the sandstone is ambiguous: it is part of that calendar, but at the same time seems to obscure it, and to hold it in suspended animation.

Yet the concrete along the West Shore shows its own processual history. Different attempts have been made to secure the coast with concrete at different times: concrete blocks cast separately and placed in gabions; concrete cast in situ. And concrete bears the traces of the process of its manufacture and the materials used to shape it. The timber framework used to cast concrete leaves the impressions of grain running across the seawall, like an expanse of wooden panelling, while hessian sacks filled with cement and left to plug gaps waste away in the sea water, leaving only their impression in the solidified cement (and occasional threads of sacking in the crevices). In many locations, the concrete laminations follow the same bedding as the flagstone, implying a human participation in the geology rather than a contradiction of it.

Varied concrete defences on Stromess’ West Shore, photo by Richard Irvine

This is Orkney’s Anthropocene bedding. It challenges us to pay heed to the fact that we are living in a geological epoch of our own making. In August 2016 a working group of the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy announced that they would formally recommend the inclusion of the Anthropocene epoch within the International Chronostratigraphic Chart, more commonly known as the Geological Time Scale. The search continues for the most appropriate stratigraphic marker indicating the presence of the Anthropocene in the geological record. Concrete is surely a good candidate. As Jan Zalasiewicz and Colin Waters, members of the Anthropocene Working Group, have argued, concrete is a “conspicuous” reminder that humans have made “a significant addition to Earth’s inventory of rock types”. And as it makes visible the impact of humanity’s short timespan on the deep time of earth’s planetary history, it also reaches that impact forward in time: the production of concrete is one of the biggest contributors to human Carbon Dioxide emissions, both through the use of fossil fuels to heat the kilns used to heat up limestone, and through the direct release of Carbon Dioxide as Calcium Carbonate is broken down into the Calcium Oxide used for cement. A particularly nasty feedback loop: our attempts to secure our built environments contribute to the climatic changes which not only threaten those very environments but also the future survival of many of the species that dwell on this planet.

Detail of concrete defences on Stromness’ West Shore, photo by Richard Irvine

Concrete’s work punctuating time, buying time, somehow locking it in – at least for a while – tells us something about the human relationship with the fluidity of land and sea. This fluidity is well captured in Orcadian folklore of ‘Hether Blether’ and other “islands that come and go” – the idea that sometimes, in the humid summer days, you catch a glimpse of what seems to be land rising out of the sea, just before it vanishes. Islands that are not on any map, but you could have sworn that you saw them. Islands that appear and then disappear into the sea: from a deep time perspective, all of Orkney is Hether Blether.

Historically, there have been many stories of this type in Orkney: Walter Traill Dennison (1893) describes stories of islands hidden from view except to those with eyes that see the unseen, to which shape-shifting ‘finfolk’ took those who loitered near the coast; while Robertson (1924) relates the tale of a fisherman who reaches the shore of an unknown island appearing out of the mist, where he finds his daughter, believed lost many years before when she went to cut the peat and never returned home. The stories surrounding Eynhallow, between the mainland and Rousay, are some of the most evocative here: once a coming-and-going island, home to finfolk, it was only made solid when it was freed from the finfolk with consecrated salt, winning over the island for Christendom. And we’re still trying to win over islands that come and go, making solid footing for humans: the presence of concrete in the geological record is testament to that.

But when I told the story of Eynhallow in the presence of the West Shore sea defences during our Festival of Deep Time, someone came up to me afterwards: “ah, but the finfolk won in the end, didn’t they? After all, it had to be abandoned. There’s no-one lives there now.”