Ode to Stromness Museum

To celebrate the Festival of Museums 2017, the small but richly furnished museum of Stromness requires due recognition both for the role it played in Orkney’s natural history, and for the curiosity it generated for many a layperson and expert to enquire of our temporal relations within our environment; an exploration of Deep Time.

Deep Time is a concept initiated by James Hutton in 1788 that proposed that the Earth was a lot older than 6,000 years, as most people thought at the time. It was an odd concept that challenged the place of both God, and of Man, something that many of the museum collectors either grappled or felt comfortable with. The Earth is now thought to be roughly 4.5 billion years old, a number that is hard for humans to grasp. For someone whose life expectancy is usually less than 100 years, it’s nearly impossible to imagine something so vast as geological or deep time. It was romanticised in the 19th century, often regarded as sublime in nature. Hutton’s extensive work opened the doorway to Charles Darwins writing of On the Origin of Species (1859), creating new ideas and theories around our relationship with time. Deep Time as a term was not coined until 200 years after its first description. John McPhee officially coined the term in his 1981 book Basin and Range, saying:

Numbers do not seem to work well with regard to deep time. Any number above a couple of thousand years—fifty thousand, fifty million—will with nearly equal effect awe the imagination.

McPhee went on to describe our place on the geological time scale with this metaphor:

Consider the earth’s history as the old measure of the English yard, the distance from the king’s nose to the tip of his outstretched hand. One stroke of a nail file on his middle finger erases human history.

We have a clear curiosity about nature, time, and increasingly our role in it, but this has been reignited lately with discussion around the Anthropocene. Established in 2016 by the Anthropocene Working Group, this new age of man indicates that we are having irreverabily and gigantic influences on the geology of the future. As future species dig down through the strata they will find plastic carrier bags, man-made chemicals, and vast movements of land and water that were not a result of natural processes. They concern is that we will have a record within the deep time scales, as never seen before, as we engage with the landscape in different ways. Whilst humans’ relations with the environment can be seen as destructive, it can also be driven by curiosity and interest. David Farrier at Edinburgh University, recently described deep time as ‘not an abstract, distant prospect, but a spectral presence in the everyday’.

It is the ‘mere’ everyday that is so important for Orkney’s tale of deep time. Starting from 1529 accounts have been written on Orkney, mostly home grown but often with astonishing links to celebrity scholars and even royalty. From the most notable is Rev. James Wallace (minister of Sanday & St Magnus Cathedral) who gathered material on Orkney at the request of the Scottish Geographer Royal to Charles II. His son later wrote up these materials. In 1700 John Brown a ‘wondermonger’ wrote A brief description of Orkney, Zetland, Pightland Firth and Caithness in 1701. However, both Wallace and Brown were isolated figures.

It really was the work of Reverend George Low who arrived in 1768 as a 21 yr old student that established the culture of natural history on Orkney. Low made meticulous observations, even meeting with Sir Joseph Banks, president of the Royal Society in London on his way home from Iceland. Low set out on his tour on Orkney and Shetland, a famous Northern tour, to make significant discoveries and provide detailed observations of the Orcadian landscape and life. However, his life ended tragically with his wife dying and his work largely being plagiarised, especially by a certain Mr Pennant who he met years earlier. Another notable scholar was Dr Patricl Neill (1776-1851), Secretary of the Edinburgh Natural History Society. By 1830, Orkney was well established on the itinerary of serous travellers, explorers, and natural historians, and most revolved around the town of Stromness.

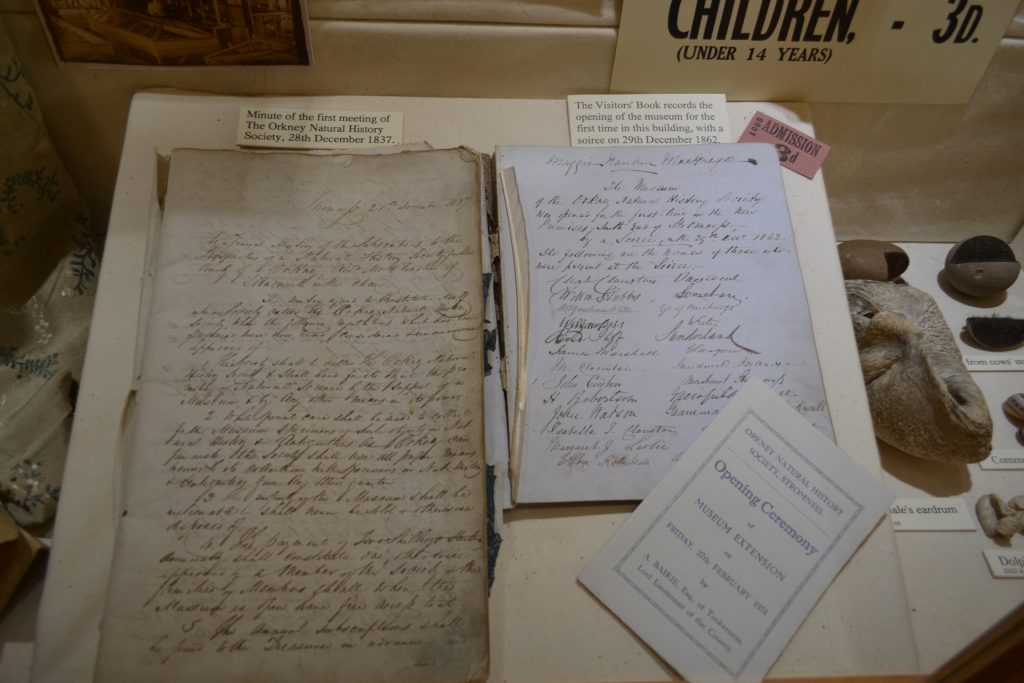

Charles Clouston, minister of Sandwick, like Low contributed significantly this field. He was both the minister and local doctor, but also pursued interests in archaeology, geology and meterology, ornithology and botany. His work was at an exciting period and led to the Orkney Natural History Society being inaugurated in December 1837. So important was the event that folk turned up over the mid-winter festivities to launch the Society that was based in what is now the Stromness Museum. Closton was president and it had a strong membership over 150. Only 6 years later the perhaps rival Natural History Society of Orkney was established in Kirwall with the annual report stating:

the study of natural history is both interesting and instructive… is eminently calculated to improve the taste, enlighten the mind and lead the contemplative student to recognise, in the delicacy of structure and adaption of parts to the purpose intended, the finger of a being possessed of unerring wisdom, and infinite power.

1840-1860 was an age of co-operation, not only between naturalists, but other professionals and amateurs. However, there were problems with ever growing museum collection and housing this in Mrs Fett’s large room at a property next door to the Subscription Library in Victoria Street. Clouston remained president until his death in 1884.

Documents for the opening ceremony of the the Orkney Natural History Society in 26th December 1837

Two key scholars departed Orkney: William Baikie (1825-1864) a ship-surgon and philologist, and Robert Heddle (1827-1860) botanist and arthioloigist. Together they printed the first part of the Histroia Naturalis Orcadensis. Their departure led to the eventual demise of the Orkney Natural History Society some 10 years later.

Meanwhile there were geologists studying the rocks, following in Huttons footsteps. One was a Shetland born Robert Jameson. Giving up surgery for geology he surveyed Orkent declaring it ‘ the most interesting journey he has ever made’. In 1804 Jameson because Professor of Natural History at Edinburgh, who taught geology to Charles Darwin. However, rather than an inspiration Darwin declared Jamesons’s lecures so dull they make him determined to never read a book on geology! It is staggering to think this may have impinged of Darwin’s love for Geology and his theories of evolution that tie so closely with those of uniformitarianism and catastrophism as recored by Charles Lyell (1797-1875) in his Principles of Geology, published in three volumes during 1830–33.

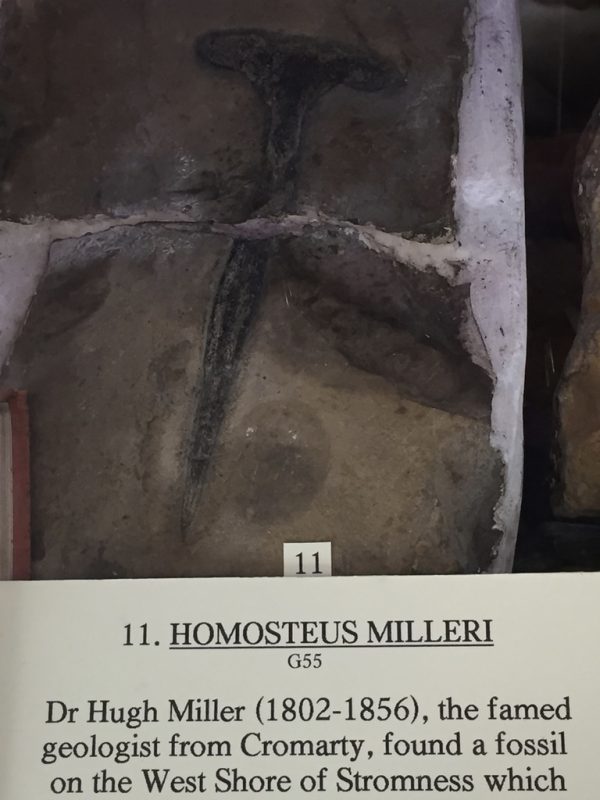

The Homosteus Miller Fossil. Photo by Carina Fearnley – Stromness Museum

Darwin had connections with Orkney in a few guises. It was Darwins discussions with Hugo Miller who came to Orkney to do geological research that led to the development and acceptance of the theory of evolution. Miller (1802-1856) was a geologist and writer he published The Old Red Sandstone (1841) and Footprints of the Creator (1850) of most note. He also found the fossil named after him of Homosteus Milleri that now sits in the Stomnes museum, one of a kind, a key link in the evolutionary pathway.

Miller held that the Earth was of great age, and that it had been inhabited by many species which had come into being and gone extinct, and that these species were homologous; although he believed the succession of species showed progress over time, he did not believe that later species were descended from earlier ones. He argued that all this showed the direct action of a benevolent Creator, as attested in the Bible. It was most likely that this view point spurred numerous heated conversations with Darwin.

This small snapshot from the late 18th century highlights that Orkney was far from being remote in the movement of natural sciences, it was in fact very much central to the debate. With links to Royal Societies in London and Edinburgh, links globally to scholars and rich amateurs, and a dynamic population that ventured the seven seas bringing back their treasures and findings, Stromness is a treasure trove of articles, all to be discovered in the museum just along the Stromness shore.

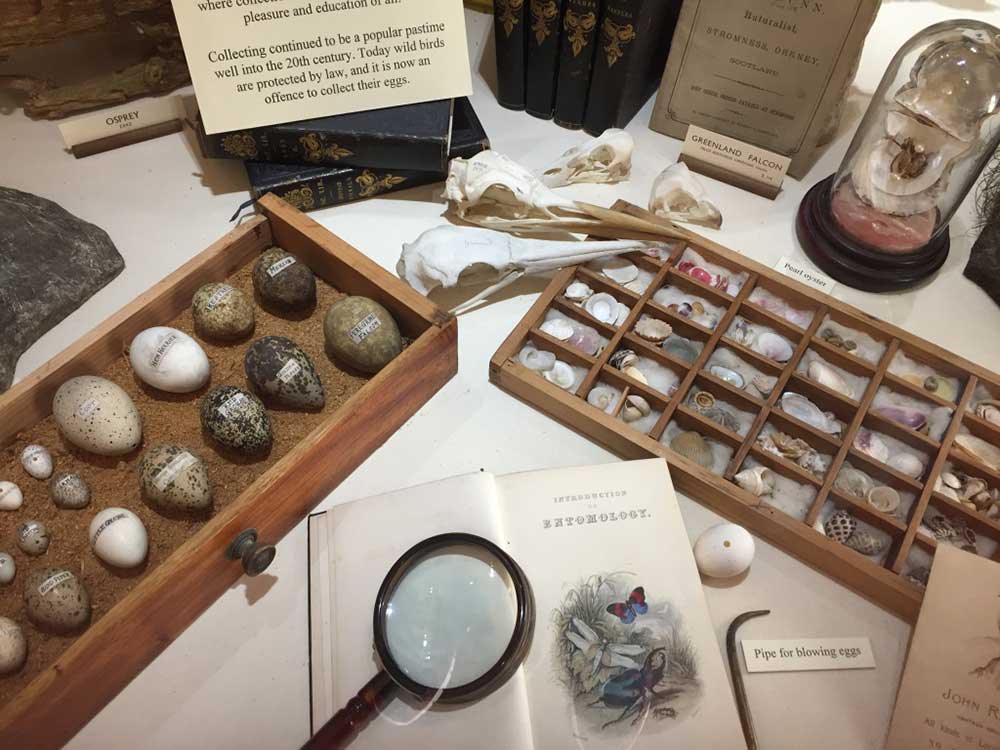

The Victorian Collectors Delight at Storminess Museum. Photo by Carina Fearnley

But it was also a dynamic coming together of minds, curious about nature, our place within it, and varying scales of time that enlightened our understnading. It wasn’t just the expertise, it was about the amateur, the bringing together of different disciplines; both inter and multidisciplinary; like the many people before, the role of polymaths that still resonate on Orkney today. Local scholarship and expertise flourished at the turn of the century as many others continued the foundations laid by others in the past, leading us to the work of Magnus Spence and Robert Rendall, a key figure in a long lineage of natural scientists. Rendall states:

Orkney inherits a tradition in natural science going back into the late 17th Century. During the early decades of our own it flowered into a brilliant group of students, many of whom ewxed professional distinction: their names are household among us. Others could be added of men eminent in their own professions and of resident local naturalist who kept alive the earlier tradition. Less generally know, however, except to keen naturalists and Orkney book-lovers, are certain 19th century professional men, doctors of medicine or ministers of the gospel, who brought to their studies of nature the enthusiasm of the amateur and something of the practiced skill of the expert.

It was in this 20th century that the subject of ecology bloomed and Rendall brought such poetic joy to the environment in which so many of the Stromness Museum items resided in. This small but special museum deserves recognition for its contribution not just to natural history, but to science, literature, and identity – the spirit of the Orcadian Natural Historian. You can still see them, walking along the shores.

Prehistoric Monster

Emergent from the deep

Hoy rears her saurian form.

Stromness lies asleep.

Robert Rendall, Collected Poems, 2012. Edited by John Flett Brown and Brian Murray.

We would like to extend our thanks to Stromness Museum for all their support and interest during our Deep Time Festival and research.