Story Time

Stories of time surround us, found encrypted in the landscape and people around us. Stories of deep time, stories of ancient peoples, stories of survival, and stories of love and pain. One could be forgiven for thinking time is a story itself. Time, that multi dimensional thing. A thing? That seems a bit harsh yet it is so hard to describe that it still perplexes physicists and cosmologists, even Einstein only scratched the surface. What is time? Some say it is:

- what clocks measure (Albert Einstein, Donald Ivey, and others)

- what prevents everything from happening at once (physicist John Wheeler and others)

- a linear continuum of instants (philosopher Adolf Grünbaum)

- a certain period during which something is done

- a continuum that lacks spatial dimensions

Yet, time is relative, a non constant, a dimension that is yet to reveal its secrets as we continue to piece together the scraps of evidence on how the universe, earth, and life came into being. The deep time of the cosmos is unfathomable as we still wonder over the origins of the universe, where it’s boundaries lie, and where the universe sits. Can we think beyond our container mentality? Seemingly not, the ultimate sublime.

As we sit here staring into the night sky, packets of time reach us as twinkling of stars from far off in the Milky Way or our neigbouring galaxies, with stories of the birth, life, and death of stars long past. Some of these stories are older than the earth itself, seeing back millions of light years (light travels at a velocity of 461 million miles per hour), time packaged in a photon, a wave, that ripples into our eyes as our brain tries to interpret its source, often just baffled by its beauty, rather than its story of time.

Yet, day to day we struggle to even read the stories of time that are beneath our feet, or of the people we greet in the street. The fine millimetre scale of rocks hides thousands of years of slow processes, a constant uniformitarian approach. The slow but gradual daily process of rivers flowing depositing grains, to the slow tectonic movements of centimetres per annum, to the evolution of life are nothing spectacular in itself, but over time these processes generate stories of the landscapes and of our Earth. From oceans, to deserts, to mountain ranges, to islands, to coastal rocks providing new sediment to repeat the process, time seems ever a cycle. The principle of uniformatarism documented by Charles Lyell (1830-1833) in the Principles of Geology is the mantra of all geologists; the past is the key to present, all laws and process are constant across space and time. But indeed this key relies on our interpretation of the past, the evidence we find, and the way we try and decipher it. Geology has always been more of an art than a science, the story telling of deep time. Punctuated through these steady processes are the catastrophes, the small weather storms, through to the tsunami (Storegga Slide), meteorites (Stoer Bay in NW Scotland), to volcanic events and mass extinctions (including the one that contributed to the extinction of the dinosaurs at the Cretaceous–Tertiary boundary). Changing everything these catastrophic events break the natural flow and process as nature finds another way, another route to survival as geological epochs end with violent and sudden natural catastrophes. Georges Cuvier, who first discussed catastrophism in the early 19th century, avoided religious or metaphysical speculation in his scientific writings, despite the obvious biblical writings that discussed catastrophic events. A key difference between catastrophism and uniformitarianism is that uniformitarianism requires the assumption of vast timelines, whereas catastrophism does not. Today most geologists combine catastrophist and uniformitarianist standpoints, that Earth’s history is a slow, gradual story punctuated by occasional natural catastrophic events that have affected Earth and its inhabitants. But what is this instinct of survival that is uniquely impressed in both the life and landscape of our planet, our home? This desire to survive to scale the next era of time? Time is both a constant punctuated by key tipping points.

Time, what is time? This was my favourite question at school, every physics lecture ended up a debate on what time is, much to the joy of our teacher:

Time = Distance / Speed

or Time Dilation t = t0/(1-v2/c2)1/2

where: t = time observed in the other reference frame / t0 = time in observers own frame of reference (rest time) / v = the speed of the moving object / c = the speed of light in a vacuum

or the equation of time that describes the discrepancy between two kinds of solar time:

Animation showing equation of time and analemma path over one year (taken from Wikipedia).

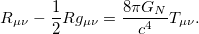

The general theory of relativity by Einstein is captured by a deceptively simple-looking equation; essentially the equation tells us how a given amount of mass and energy warps spacetime:

So time is warped by mass and energy, relative to a frame of reference, and even the time of a day (the solar time). Time is as far from being deep, as it is being shallow and temporary.

Time could be said to be nothing short of a human construct, a way for us to place order in our lives, a structure, a way to rejoice in the processes of sunrise and set, the solstices, and the Earth’s precession. Time is relative to us. Those happy moments in life when time passes by too quickly, to the sad and troubled moments when time seems to stagnate, holding back. The way humans understand time has varied significantly. The aboriginals have a different sense of time, with a less structured past, present, or future. Today in modern Western life these three tenses shape everything we do, down to the second. Yet for Aboriginals their cosmology is centred on ‘The Dreaming’ that moves across past, present and future (as taken from Edgar B. Time for God: Christian Stewardship and the Gift of Time. ERT. 2003;27(2):128-146):

The past underlies and is within the present, ‘events do not happen now, as a result of a chain of events extending back to… a beginning. They exist and they happen because that Dreamtime is also here and now. It is The Dreaming, the condition or ground of existence.’ It is sacred-past-in-the-present.

This concept of time is atelic (purposeless), significantly compressing the difference between historical time and infinity. The Dreaming, now more commonly called Creation Time, describes a detailed relation among spirits, humans, plants, animals, and the land. The land, then, embodies the Dreaming, connecting time to place.

Time by Tim Almquist (https://australiastudiescentre.wordpress.com/2014/11/04/from-linear-to-circular-an-indigenous-view-of-returning-home)

In Orkney time is littered over the landscape, fixed in places, stories both old and new. The richness of time is almost overwhelming to the point it is hard to stop still and take it in. However, there are the stories of those people like the Picts that we will never know, unrecorded, and forgotten in the abyss of time. So perhaps time isn’t just about stories, those stories have to be recorded. Like the fine grains in a rock, without art, writings, and folklore of civilisations past, it is time lost, a black hole never to be seen or heard of again. Time is a recording, a piece of data, whether a photon or a shrine. As we construct stories we construct time, we give it meaning, we give it purpose. Without this data time is just lost, meaningless, a sea of dark matter that is undiscoverable and mythical, for now at least.