Orkney: Late Medieval Dress

This article discusses Late Medieval Dress in Orkney. The visual evidence for any clothing from the Norse and medieval period in Orkney is minimal. There are small statues of St Olaf, St Magnus and St Rognvald, originally from the Cathedral of St Magnus in Kirkwall, which show the three saints in standard dress of high-ranking individuals from c.1300. St Magnus and St Olaf are wearing long sleeved gowns which fall from the neck in folds, and the latter has a heavy belt slung low from his waist which he is holding with his left hand. Both of them also have cloaks hanging from their shoulders tied with a cord across the upper chest. On the St Olaf figure the cord hangs down his torso, ending in a tassel, while Magnus holds the cord of his cloak with the fingers of his left hand in a mannered fashion. Both are distinguished by their different headgear, St Olaf wearing a tall royal crown, Magnus with a circlet around his forehead which signifies his noble status. Olaf holds a long spear in his right hand while Magnus is holding the sword of his martyrdom in his right hand. Their footwear appears to take the form of soft shoes, presumably leather, with pointed toes in the case of Magnus. These are remarkable surviving images of the two northern saints, but an even more remarkable survival is the statue which was located high up on the 16th-century Tower which Bishop Robert Reid added to the Bishop’s Palace in Kirkwall.

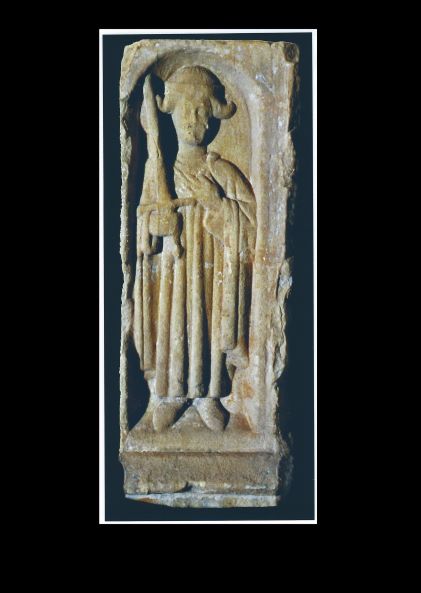

This small statue has now been removed to the Orkney museum (with the statues of St Olaf and St Magnus), but it must have originally been in the Cathedral of St Magnus and was put in a niche on the Moosie Tower after the Reformation. This indicates a particular reverence for the statue and it has been suggested that this was because the figure represented Rognvald Kali Kolsson ‘the Holy’, the nephew of St Magnus who succeeded to the earldom in the 1130s. He founded and endowed the Cathedral in memory of his uncle. The statue represents a nobleman, and also an earl as is evident from the circlet or garland which is around his brow. He wears a short tunic which hangs below the knee, and which is tied at the waist with a belt from which one end hangs down. Although the details of the dress are much worn, there is evidence that he has a cloak over his shoulders, with a short cape round the back. As with the statue of St Magnus, this cloak is fastened across the chest, and is held with the fingers of the right hand. The sleeve of the tunic hangs down from his right wrist. Beside the right foot is a low stool which has been interpreted as a foot-stool for use when a harp or lyre was played. This is particularly associated with the object which rests on the stool and which most probably represents the harp which Earl Rognvald was known to play. It is recorded in the Orkneyinga saga that he boasted of his accomplishments, among which was his ability to play the harp and to make verses. Earl Rognvald’s verses are recorded in the saga and show that he was a skilled skaldic poet.

It is perhaps not surprising that the two Orkney saints and the sainted King Olaf of Norway are part of the sculptural treasures of the islands. What is surprising is their survival through the upheaval of the Reformation. The explanation lies in the fact that the Reformation was not so destructive in the islands as in other parts of Scotland, and in the islanders’ particular reverence for their saint-earls. In Scandinavia in general the Reformation was less destructive than in other parts of north Europe and several statues and depictions of St Magnus have survived in Scandinavia and Iceland, as well as many St Olaf statues.

The only other visual evidence for medieval clothing in Orkney comes from a very different medium, and from very different sectors of Orcadian society. These are the figures depicted on seals, one being the Common Seal of Orkney, and the other being a half seal-matrix showing the woman to whom the seal had belonged. The first was the seal of the community of Orkney, of which only remnants survive on 15th-century documents. It is known primarily from a reconstruction drawing made by the Danish historian and heraldic artist Anders Thiset in the early twentieth century. Such a seal would have been granted by the Norwegian crown to its island dependency, as to other Norwegian provinces. It is a significant indicator of Orkney’s position under the authority of the king of Norway, and the king’s authority is symbolised by the royal Norwegian lion on a shield which is supported by two bearers.

These two bearers are of particular significance for the clothes they are depicted as wearing. These are presumably the clothes of upper-class Orkney landowners, or ‘udallers’ who held their land according to odal right, that is with inalienable rights over family land. These were the men who ran the Orkney community, and it is likely that these bearers represent the elite few who had joined the king’s ‘hird’or retinue as liegemen. Such men are known in the Norwegian sources as håndgangne men (those who had ‘gone to the king’s hand’ and given an oath of loyalty). They are also called ‘best men’ or ‘good men’ and were organized as a brotherhood or guild with the king as patron. It is most probable that it is these royal servants who are depicted bearing the royal Norwegian royal symbol on the shield, the lion with an axe held in its paw; but these men were Orcadians first and foremost with a strong regional identity and we can assume that the dress they are wearing would represent civilian dress of a distinctive kind as worn in the islands.

It is certainly different from the dress of the bearers on the Jemtland seal, another Norwegian provincial commune seal, who are shown wearing long coats or tunics. The bearers on the Orcadian communal seal are wearing thigh-length tunics, or jerkins, and breeches, with embroidery or decoration on the cuffs, around the neck and at the bottom of the jerkin, which has a belt at the waist, and at the bottom of the breeches. The breeches hang below the knees and there are leggings on the lower legs. From another sketch of the seal, also dating to the turn of the twentieth century, it appears that the leggings or trouser hose were of woven fabric ‘arranged on the bias and sewn together to be close-fitting’. This sketch also indicates that the footwear was ‘rivlins’, that is, soft leather shoes of undressed ox hide worn in the north of Scotland, possibly shown tied at the ankle.

The head covering is a very uncertain matter, for it appears from Thiset’s drawing to be a hood, although it has also been thought that the bearers are shown bare-headed, as are bearers on other Norwegian seals. It can hardly be a helmet as there are no other indications of military accoutrement. Headgear is certainly a distinctive feature of the presumed female owner depicted on the half-seal matrix recently found in Deerness, in the East Mainland of Orkney and mentioned above. This must have belonged to a member of the Orkney earldom family, or of the Norwegian aristocracy, for the ownership of seals was restricted to the high-born, particularly at the time of the seal, which is dated to c.1300 or possibly earlier. Identification of the female owner is problematical, for the inscription only partially survives. She is depicted kneeling with her hands clasped prayerfully in front of her, and it is presumed that a saint in the upper half of the matrix would have been the object of her devotion. The dress or cloak which she is wearing is long and covers her lower legs. It may be shown divided at the front or else with a long sleeve hanging from her forearm down to her knee. The most distinctive feature of her attire is the hat or head-gear with ribbons or streamers shown flowing out behind the head. There are faint traces of a cheek strap which held the hat in place coming down the side of her face and under her chin. This is a fashionable contemporary style of head-covering but it is a very unusual survival of such an image in Scandinavia, and most especially in Orkney.

This discussion of the dress of which we have evidence from medieval images in Orkney was written for inclusion in the Encyclopedia of Medieval Dress and Textiles but it is worth reproducing in an Orkney context to make the point that these statues and seal images are the only depictions of medieval Orcadian figures that have survived. Moreover the seals provide the only surviving medieval representation of secular men and, in the case of the Deerness seal of a secular woman, who was most probably from Orkney, or who had some close association with Orkney.

This was first published in the online edition of Encyclopedia of Medieval Dress and Textiles, 2016 (edited by Gale Owen-Crocker, Elizabeth Coatsworth, Maria Hayward).

Fig.1a Statue of St Magnus, now in the Orkney Museum, Kirkwall.

Fig.1b Statue of St Olaf, now in the Orkney Museum, Kirkwall.

Fig. 2 Statue of St Rognvald, formerly situated in a niche on Bishop Reid’s Tower, Kirkwall, now in the Orkney Museum, Kirkwall.

Fig. 3 Drawing of the seal of the community of Orkney probably by Anders Thiset, Danish historian and heraldic artist: early 20th century (copied from Clouston 1932, facing p. 276).

Fig. 5 Broken matrix of a medieval seal found by a metal detectorist in Deerness, East Mainland, Orkney (Courtesy Orkney Islands Council).