The Finnfolk

Text of a public talk Dr Andrew Jennings gave at the Shetland Museum

25th of March 2010

I’d just like to start this talk with a warning! I hope there’s no one here of a delicate disposition, because this talk will include sex and violence! Let’s begin with a bit of the latter. Here’s a violent little story:-

I’d just like to start this talk with a warning! I hope there’s no one here of a delicate disposition, because this talk will include sex and violence! Let’s begin with a bit of the latter. Here’s a violent little story:-

‘One fine morning when the Foula men came down to the shore, they found that a number of Finns had landed, and were lying asleep on the rocks below the banks. The Foula men armed themselves with stones, and attacked the Finns with great fury. The Finns jumped up in alarm, and getting into their skins, plunged into the sea, leaving one of their dead on the shore. They drew together in the Sea, calling to each other and lamenting the death of their comrade, beating their breasts with their hands and enquiring of one another who it was that had been killed. One replied that it was ULGA-NA-MEIGA, the son of GEOGA, and she was a widow and had lost her only son’(R. Stuart Bruce Old-Lore Miscellany Vol.IX Part IV Oct.1933)

Who, or what, were these unfortunate Finns? I hope the answer will be clear by the end of the talk!

2.0 Quick cultural history – Mixed Norse and Scottish folklore

First, here’s a quick overview of the nature of the folklore of Orkney and Shetland.

The folklore of Orkney and Shetland reflects the mixed origins of the Northern Islanders. In the 9th century, the Isles were settled by Norwegians, who either replaced the original Celtic inhabitants or blended with them (the jury is still out). These Norwegians created a Norse society which remained in the islands long after they were granted to the King of Scots in 1468 and 1469. The insular Norse language, called Norn, survived until at least the mid-18th century. It was completely replaced by a heavily Scandinavianised form of the Scots language, which was brought to the Isles by Scottish settlers, who had already arrived in large numbers by the end of the 16th century. The mixed society developed a mixed folklore with both Norse and Scottish elements.

Alan Bruford an acknowledged expert on the folk tales of Shetland, has shown that, when it comes to fairy-legend types, the Scottish contribution to Shetland cultural heritage is greater than the Norse. For example, although the fairies are usually called trows, which comes from the Norse word troll, the stories about them are mainly Scottish legend types, often strikingly similar to stories from Gaelic tradition, despite the often heard refrain in Shetland that Gaelic culture is alien to the Isles.

On the other hand, when it comes to supernatural beings, there is a strong inheritance from Norse. Both land and sea were believed to be inhabited by such beings and these have mainly Norse names. For example, there are the aforementioned trows. There are also njuggles (water horses from the Norse nykkr) and grϋlies (ogresses who live in holes and bugbears who bide in coal bunkers from the Norse grýla).

- Magical Finns in Scandinavian Tradition

We will see that the Finns, as an uncanny, supernatural people, are another survival of Norse cultural heritage, although they have been transformed somewhat in the island setting. However, before I delve into the stories about the Finns in Orkney and Shetland, I’d like to provide some background by looking at the traditions surrounding the Finns in Scandinavia.

It is important to point out that in the folklore of both Sweden and Norway, the aforementioned Finns are actually the Sámi or Lapps, the Finno-Ugric speaking indigenous population of Northern Scandinavia, rather than the inhabitants of modern Finland. The word Finni or Finnr in Old Norse glossed both Sámi and Finn, and Finn still means Sámi or Lapp in Norwegian dialects today.

In Norwegian and Swedish folklore the Finns are renowned as magic-workers. Amongst their many magical skills is the ability to voluntarily turn into wolves or bears. For example, in a story from Dreyja in Nordland:-

They once shot an unusually large bear up in Dreyja. While they were flaying the animal, a young Finn came by. He stopped and watched them for a while. Suddenly he burst into tears. They had killed his grandfather, he said.(Kvideland and Sehmsdorf Scandinavian Folk Belief and Legend 1988:79)

Finns could also send their spirits out of their bodies to complete various tasks. Here is a good example of the magical skills of a Finn from a story called the Finn Messenger (which has the Migratory Legend number ML3080):-

Neri Olavsson lived at Sönstveit for a while. His wife ran the farm while he was at sea. A strange thing happened to him one Christmas Eve, while he was off the China coast, and, according to Anne Godlid, it was this.

It had been necessary for him to leave his wife while she was with child, and he was quite worried about her and very home-sick.

“If only there was some way of finding out how things were at home!” he said to one of his shipmates, a sailor who happened to be a Finn and was said to know more that the others. “! Had to leave my wife when she was with child,” he said, “and Heaven knows how it’s turned out!”

“What’ll you give me if I bring word from home for you tonight?” said the other.

“You certainly couldn’t do that!” said Neri.

“If you’ll give me a pot of spirits, it’s in order!” said the sailor.

“I’d gladly give you five, if anything like that is humanly possible,” said Neri.

“Well, if you have something at home you’d recognize again, I’ll fetch it,” said the sailor.

Why yes, they had a queer silver spoon that had come from the huldre-folk and which they never used. It stood in a crack in the wall over the window. “Fetch that!” said Neri.

The sailor said they had to stay as quiet as mice as long as it lasted, and this they promised to do. Then he chalked a circle on the deck and lay down inside it just as if he were dead. They all saw how he became paler and paler and lay there without moving a limb until the onlookers were downright terrified. He lay this way for some time, but suddenly he gave a start, got to his feet, and he was holding the spoon in his hands.

“Here’s your silver spoon again,” he said to Neri. “Now I’ve been to Sönstveit.”

“So I see, “ said Neri; he recognised the spoon. “How was everything there?”

“Oh just fine,” said the sailor. “Your wife’s had a lovely big boy. Your mother was sitting inside a black house, spinning on a distaff. She was a little poorly, she said. But your father was down on his knees, out by the chopping block, cutting wood.”

Neri wrote down the date and the hour right away.

When he came home, he found out that everything was just as the sailor had said.

“But the old silver spoon has disappeared!” they said. “One day there was a rumbling so the whole house shook. We never were able to figure out what it was, but since then we haven’t seen anything of the spoon!”

“Well, here it is,” said Neri. “It’s been all the way to China!” (Christiansen Folktales of Norway 1964:40-41)

It’s extraordinary that an almost exactly similar version of the The Finn Messenger tale also exists in Shetland. Here it is called the Tale of Peter White and the Finn (Nelson Shetland Folk Book V 1-3). Peter White, who lived in the north croft of Smockwell, in Tingwall, was on a voyage across the Atlantic. In return for a pot of spirits, a Finn promised to go into a trance and report how things were at home. He also brought back a silver spoon, which had been gotten from the trows as evidence for his visit. When Peter returned home, his family told him they remembered a night when the house was struck by a gust of wind and the silver spoon went missing. Peter in commemoration had his son John White baptised with the middle initial C, for Cast, the Christian name of the Finn.

In addition to the folklore of Norway and Sweden, the Icelandic sagas also highlight the magical reputation of the Finns, or Sámi. These ideas must have been brought to Iceland as part of the intangible cultural heritage of the Norse settlers. The respected Icelandic scholar Hermann Pálsson has studied how the Sámi were represented by the Icelanders. They are seen both as highly skilled wizards and practitioners of witchcraft, and as teachers of magic. According to Snorri Sturluson, the terrifying witch-wife of Eiríkr ‘Bloodaxe’ Queen Gunnhildr, learned her magic craft from two Sámi magicians. Pálsson also follows the Swedish folklorist Dag Strömback in suggesting that the Old Norse magical practice of seiðr, a shamanic ritual practiced by the völva ‘seeress’, was learnt from the Sámi. He also suggests that the völva’s related practice of útiseta ‘sitting alone in the open air after nightfall to commune with the trolls’ was also a practice of Sámi origin.

In Orkneyinga Saga there is an example of the practice of útiseta. It was said of the incorrigible Orcadian warrior Svein ‘Breastrope’ that: ‘He was keen on the old practices and had spent many a night in the open with the spirits.’

In the sagas, as in folklore, the Sámi were believed to be able to shape-shift into wolves and bears. However, they were also able to change into sea-mammals, such as whales and walrus.

InHeimskringla it was almost certainly a Sámi who was sent by King Harald Gormsson of Denmark in the form of a whale to Iceland, to see whether Iceland was worth invading. He was driven off by the Icelandic land-spirits and Harald abandoned the idea.

In the Saga of Halfdan Eysteinsson, King Fiðr turns himself into a walrus - as it says in the saga:-

Fiðr, king of the Finns...turned himself into a walrus, and ran up on top of those who were fighting against him. There were fifteen men under him, and all were killed. The dog Selsnautr ran toward him, and tore him apart with his teeth, but the walrus struck his jaw to pieces. The dog Karlsnautr ran into the jaw, and all the way down into the belly and tore him inside, and cut out his heart.

InVatsndæla Saga there is a version of the Finn Messenger tale. It records that Ingimundr the Old, who lived in North Hålogaland, offered two Finn wizards butter and tin if they would go on a magic ride to Iceland to retrieve an image of the god Freyr and come back with a description of the land. They failed to retrieve the image but did return with a glowing report of the landscape.

In addition to the sagas, we have a very early account of how the Sámi were regarded, in the 11thc century Norwegian book the Historia Norvegiae. Here a Sámi wizard sends out his soul in the form of a whale to accomplish a task. It is likely that this is the earliest written evidence of a Sámi ‘shaman’ or noaide practising his art. However, as the only extant version of this text was copied in Orkney in around 1500, it is also reasonable evidence that knowledge about the magical practices of the Sámi was known in Orkney. In the text, you’ll see the word gandus this is a Latin form of Old Norse gandr ‘magic’ or more exactly ‘the soul or breath sent out from the body to work magic’.

[TheSámi’s]intolerable ungodliness will hardly seem credible nor how much devilish superstition they exercise in the art of magic. For some of them are revered as soothsayers by the foolish multitude because whenever asked they can employ an unclean spirit, which they call a gandus, and make many predictions for many people which later come to pass. By marvellous means they can also draw to themselves objects of desire from distant parts and although far off themselves miraculously bring hidden treasures to light.

Once when some Christians were among the Lapps on a trading trip, they were sitting at table when their hostess suddenly collapsed and died. The Christians were sorely grieved but the Sámi, who were not at all sorrowful, told them that she was not dead but had been snatched away by the gandi of rivals and that they themselves would soon retrieve her.

Then a wizard spread out a cloth under which he made himself ready for unholy magic incantations and with hands extended lifted up a small vessel like a sieve, which was covered with images of whales and reindeer with harness and little skis, even a little boat with oars. The devilish gandus would use these means of transport over heights of snow, across slopes of mountains and through depths of lakes.

After dancing there for a very long time to endow this equipment with magic power, he at last fell to the ground, as black as an Ethiopian and foaming at the mouth like a madman, then his belly burst and finally with a great cry he gave up the ghost. Then they consulted another man, one highly skilled in the magic art, as to what should be done about the two of them.

He went through the same motions but with a different outcome, for the hostess rose up unharmed. And he told them that the dead wizard had perished in the following way: his gandus, in the shape of a whale, was rushing at speed through a certain lake when by evil chance it met an enemy gandus in the shape of sharpened stakes, and these stakes, hidden in the depths of that same lake, pierced its belly, as was evident from the dead wizard in the house.

For our later discussion it is important to bear in mind this ability of the Sámi to transform, into sea mammals – namely walrus and whales.

Continuing the marine theme, the Sámi were also reputed to be fine boat-builders. According to Heimskringla, in 1139 Sigurd Slembe when in Hålogaland:

had the Sámi construct two boats for him during the winter up in the fjord; and they were fastened together with deer sinews, without nails, and with twigs of willow instead of knees, and each boat could carry twelve men.... These boats were so light that no ship could overtake them in the water, according to what was sung at the time: --

Our skin-sewed Fin-boats lightly swim,

Over the sea like wind they skim.

Our ships are built without a nail;

Few ships like ours can row or sail."

The association of theSámi with coastal, marine habitats might seem strange to us, as we normally imagine them driving their reindeer herds across the tundra of Northern Scandinavia. However, even today there is a maritime group of Sámi, called the sjøsamer, who live along the northern Norwegian coast and have been struggling to preserve their identity and heritage. In fact nomadic reindeer herding was only one of the responses to the end of hunter-gathering amongst the Sámi around 1600, which was brought about by over-hunting.

In their hunter-gathering days the Sámi were known for their whaling and sealing, as much as for their reindeer. In the 9th century, the Norwegian trader Ohthere from the far north of Norway told King Alfred, that the Sámi paid him the following tribute:-

Ðætgafol bið on dēora fellum and on fugela feðerum and Ø hwæles bāne and on ðǣmsciprāpum ðē bēoð of hwæles hӯdegeworht and of sēoles

‘The tribute is (paid) in deer hide, and (paid) in bird feathers, and (paid) in whale bone, and (paid) in that ship-rope which is made of whale and seal hide.’

In the 11th century, the German chronicler Adam of Bremen, described how the Sámihad the ability ‘with a powerful murmuring of words [to] lure the huge whales of the sea on to the shores’.

Clearly the Sámi are surrounded bymaritime connotations. However, in the Icelandic sagas there is another important connotation. They could be described in purely mythical terms. According to Pálsson ‘the total semantic range of [the word] troll must have included the notion of a Sámi’, and particularly in the Legendary Sagas, the Sámi could be presented as quasi-mythical beings.

Völundr,the magical smith of Old Norse Religion, is agood example of this blurring of the human and the supernatural. In the introduction to Völundarkviða, he is described as sonr Finnakonungs ‘the son of the Sámi king’ but, in the poem itself, he is called vísir álfa ‘lord of the Elves’. The uncanniness of the Sámi, is also clear from the fact that Norsemen with Sámimothers could be given nick-names such as halftroll, halfrisi ‘half giant’ and halfbergrisi ‘half mountain-giant’. It is no coincidence that elfshot can be called finnskot in Norway.

Why did the Sámi have this reputation in the earlier Icelandic literature and in the later Norwegian and Swedish folklore? In the early period the Germanic Scandinavians clearly saw them as other, an odd people who spoke an odd language, and they consequently regarded them with suspicion. However, in addition the Sámi managed to maintain their traditional religion and its shamanistic practices long after the rest of Europe succumbed to Christianity. Despite Lithuanian claims to the contrary, there can be no doubt that the Sámi were Europe’s last authentic pagans. Individual Sámi continued to practise their ancestral beliefs right into the Early Modern era. In 1692, the same year as the massacre of Glen Coe, the unfortunate Lars Nillsson of Silbojokk was burned at the stake for worshipping his traditional gods with sacrifices and drumming, after the Christian God had failed to protect his reindeer.

So to recap before moving on, in the wider Scandinavian tradition, the Sámi are called the Finns. They are strange people who are renowned for working magic. They are strongly connected with maritime mammals, being able to take on the form of whales or walrus, and they can be described in purely mythological terms as supernatural beings.

4.0 Finns as Magicians in the Northern Isles

Now let us turn to the Northern Isles, where we can see many of the same connotations circulating around the word Finn. In the collections which have been made over the past two centuries of the folklore of Orkney and Shetland, the Finn presents a fascinating figure. Finns are reputed to be magicians and witches with special powers, which include amongst other things, taking animal shape, travelling very quickly across the sea, discovering things from afar and finding lost items. They can also be regarded as supernatural beings; sometimes they are synonymous with trows; at other times they have merged with the merfolk and selkies, or the sea-trows if you like.

A Finn could cross from Norwick, on the North coast of Unst, to Bergen and back between sunrise and sunset at a speed of 9 miles to the warp (the stroke of the oar) Or even more amazingly, ‘he could pass from Orkney to Norway, or from Orkney to Iceland with seven warts’ (only 7 strokes of the oar) (Traill Dennison Orkney Folklore and Sea Legends 1975:34). According to Spence people who were ‘supposed to be skilled in the Black Art, were spoken of as Norway Finns’.

The association of the Finns with magic is highlighted by the use into the 20th century of the adjective Finnie as an epithet for peculiar old women. According to Ernest Marwick, at the beginning of the century on Sanday, in Orkney, there was an old woman named Baabie Finn who was ‘reputed to have strange powers’ and it was ‘asserted her ancestors were Finns’.

In Unst, Jessie Saxby (Shetland Traditional Lore 1932:96) remembered that in 1932 she saw ‘a woman who went by the name of “Finnie”. She was very short, less than five feet in height, and very broad in the body. She had black hair and black eyes, and it was said that she “could do things we canna name,” but her doings were always of a kindly nature, “just the way o’ a’ the Finns.

In Unst, Jessie Saxby (Shetland Traditional Lore 1932:96) remembered that in 1932 she saw ‘a woman who went by the name of “Finnie”. She was very short, less than five feet in height, and very broad in the body. She had black hair and black eyes, and it was said that she “could do things we canna name,” but her doings were always of a kindly nature, “just the way o’ a’ the Finns.

There are several folktales from Fetlar about the Finns. In one of them, the farmer of Kolbenstaft had only a low fellie dek (turf wall) to protect his crops. Horses and sheep kept getting over it, much to his annoyance. One night a Finn appeared to him in a dream and said that because the farmer’s folk had been kind to him, he would be kind to the farmer. In the morning the farmer awoke to find a stone wall enclosing his land. This is the Neolithic Finnigert which traverses Fetlar from North to South. The name Finnigert looks like it might originally have come from *Finna-garðr ‘Enclosure of the Finns’ (Jakobsen, J. The Placenames of Shetland 1936:175). However, even if the original place-name specific was the man’s name Finn, it is unimportant from a folklore perspective. According to Jakobsen, the troll-myths of Fetlar are concentrated about the Finnigert dyke. In the tale, the Finns are being associated with the folklore topos of supernatural beings that carry out great building works at night. There is another example of this same topos from the 11th century Historia Norwegiae, where it says that the Picts, who are also regarded as mythical beings, were supposed to have accomplished miraculous achievements by building towns, morning and evening, but at midday they lost every ounce of their strength.

This merging of the Finns with supernatural beings is the explanation for place-names Finnie Knowe ‘The Finns’ Knoll’ in Nesting and Grunafirth and the Finnie Hadds ‘The Finns’ Burrow’ which lie in a remote glen between Boofell and the Lang Kame. Finnie Knowe is an exact parallel of the phrase Trowie Knowe. The same process can be seen in Andrew Hunter’s description of Finnister, which he suggested had something to do with the Finns, being an ‘aaful place fir trows’ (Tocher 34:275). Trows and Finns could clearly be regarded as synonymous.

In the tradition, there is a particularly close relationship between the Finns and the sea. A story from Unst tells how a Finn’s sons returned from fishing having caught and then lost a large turbot. Unfortunately, the turbot made off with the fishing line. The Finn, hearing this, disappeared. He reappeared later with both the turbot and line. He had gone a great distance to catch it. He told his sons:

‘I haed da Öra at da Ötsta wi’ Vytaberg at Tonga afore I made up wi’ im’!’(SpenceShetland Folk-Lore 1899:23)

In other words, he caught him way out to the North of Shetland. The story doesn’t tell us in what form the Finn caught up with the turbot, but as we’ll see it was probably in the form of a seal.

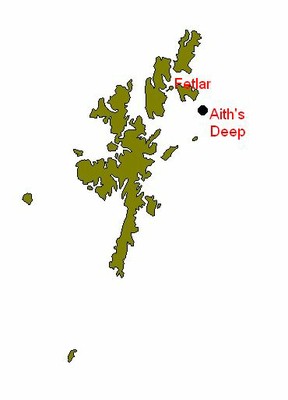

In another story from Fetlar (Shetland Folk Book 2 1951:5), a Norway Finn came across from Norway, catching fish as he went. When he approached Fetlar, he noted a particularly good fishing ground. Unfortunately, a storm blew up and the Finn was blown into the Wick of Funzie, where at the last minute he was rescued by an Aith man. The exhausted Finn in thanks told him of the wonderful fishing ground and promised:

‘ye may hae a tired back an’ a heavy hand but niver a faerd hert or a tøm boat. And so it was ,”Aiths Deep” became “Aiths Bank” and no life was ever lost going to or coming from this ground.’.

Another Fetlar tale tells of an Aith man who went to Norway. He met a Finn while he was there, who made him a wager, that he would neither taste fish nor have fresh fish in his skio ‘drying shed’ before Yule. The winter that year was so stormy that the Aith man could not go to sea even to catch bait. So it looked as if he was going to lose the wager. However, on Tammas E’en (20th December), the weather broke. As he had no bait, the Fetlar man dyed a rag in blood from his own foot and used that. It proved to be effective, because he caught an olik ‘young ling’. However, as he headed back to shore, the sea arose and threatened to swallow the boat. He used oil from a small keg to smooth the surface of the sea. But as he was crossing the ‘String o’ de Minnie Stack’ a terrible wave came rolling behind him. He seized the oil keg and threw it in the face of the wave and thereby managed to make land. On his return to Norway, the Aith man visited the Finn and reminded him of their wager and the Finn pointed to a deep scar on his brow and his broken teeth and replied,

‘I’m paid dear eneuch fir dat olik. Doo didna only smore me wi dy oil bit soved me wi dy oli hjulk’. (Shetland Folk Book 2 1951:5-6).

It had been he Finn himself who had tried to sink the boat while in the form of the huge wave.

An important motif that these two Fetlar stories share is the clear association between the Finns and Norway. This turns up time and again in the Shetland material, but is not an important feature of the Orcadian material. This is undoubtedly due to the fact that, historically, Shetland retained closer links than Orkney did with Norway; maintaining close contact long after Shetland became part of Scotland. This distinction between the two archipelagos is exemplified in a toothache charm, where the Finns are being called on to cure toothache. The Shetland version reads:

A Finn came ow'r fra Norraway,

Fir ta pit tooth-ache away

Oot o' da flesh an' oot o' da bane ;

Oot o' da sinew an' oot o' da skane ;

Oot o' da skane an' into da stane

The Orcadian version is quite different it runs:

T'ree Finnmen cam' fae der heem i' de sea,

Fae de weary worm de folk tae free,

An' dey sail be paid wi' de white monie!

Here there is no mention of Norway: the Finns or Finnmen live in der heem i' de sea. They are supernatural sea-beings with a penchant for white money, or silver.

In Shetland tradition the Finns, despite their continued relationship with Norway, also coalesced with the supernatural beings of the sea, just as they merged with the trows on land. Indeed, it’s as sea-beings that the Finns are best known in tradition.

So now let’s look at the supernatural inhabitants of the sea.

- Sea Trows - Seal Folk, Merfolk and the Finns

Supernatural denizens of the Deep were a feature of Norse folklore. The Medieval Norse believed the Ocean was inhabited by supernatural beings - creatures like the monstrous márgygr ‘sea-giantess and the terrifying Jörmundgandr or Miðgarðsorm ‘the world serpent’ which encircled the Earth. The márgygr would be seen off the coast of Greenland before violent storms. It was described in the 13th century Konungs Skuggsjá ‘King’s Mirror’ as follows:

[The márgygr] appears to have the form of a woman from the waist upward, for it has large nipples on its breast like a woman, long hands and wavy hair...it rarely appears except before violent storms...The monster is described as having a large and terrifying face, a long sloping forehead and wide brows, a large mouth and wrinkled cheeks.

It appears to be a grotesque form of the mermaid, and indeed Lehn & Schroeder (2004:132) suggested that Norse descriptions of the márgygr may have influenced the evolution of ideas surrounding the modern mermaid, although the female-fish hybrid may go back to Classical tradition. Lehn & Schroeder have also argued that the márgygr was a real phenomenon, namely a short-range mirage of common Arctic sea mammals, like a killer whale. Be that as it may, she must have been known outside of Norse Greenland because she also entered the folklore of the Hebrides. Here the word márgygr has been Gaelicised to Muireartach, through an odd contamination with the Old Gaelic name Muircheartach. She was also an exceedingly hideous female:

The teeth of her jaws crooked red, In her head there glared a single eye.

TheMuireartach was the foster-mother of Manus King of Lochlann, according to the old Gaelic Ballad and she may have been a personification of the Ocean.

The Norse ‘world-serpent’Jörmundgandr also seems to have entered Gaelic tradition. It probably lies behind the Gaelic sea-monster the Mial mhòr a’chuain ‘the Great Beast of the Ocean’, which has the other indicative name Cuartag mhòr a ‘chuain ‘the great Encircler of the ocean’. This creature haunted the seas and was only satiated if he had eaten seven monsters, each of which had eaten seven great whales!

The existence of a reflex of the márgygr in the Hebrides is reason to suppose that she was also known to the Norse inhabitants of the Northern Isles. There is clearly a folk memory of Jörmundgandr in the Orcadian story about the Mester Stoor Worm, which was still known to the Orcadian peasant in the 19th century. Karl Blind also found a trace of this belief in 19th century Shetland.

These titanic monsters were not the only supernatural inhabitants of the sea in Norse tradition. There were also beings more human in scale, who just happened to live beneath the waves, such as the marmennill ‘sea-mannikin’ who appears in Landnámabók. It is creatures of this scale that have survived more obviously in the folklore of the Northern Isles, such as the agreeable Seal-Folk (or Selkies) and the Merfolk. The 19th century Orcadian folklorist Walter Traill Dennison, whom we have to thank for recording the story of the Mester Stoor Worm, considered the Seal-Folk and Merfolk to be different beings. He referred to local informants to that effect. Clearly in 19th century Orkney a distinction was being made between the two tribes. However, in reality, the same stories are told about both groups, and when their characteristics are compared one can see they are different aspects of the same supernatural inhabitants of the sea. Indeed, the essential equivalence of the two was recognised by earlier scholars: Jessie Saxby (Shetland Traditonal Lore 1932:138) said, ‘Mermaids were known as Sealkie-wives and their seal lovers were said to be fallen angels in a hateful disguise,’ while Samuel Hibbert (A Description of the Shetland Islands 1891:298) wrote of mermen and merwomen that:

‘One shape that they put on is that of an animal human above the waist, yet terminating below in the tail and fins of a fish, but the most favourite form is of the large seal or Haaf-fish’. Hibbert goes on to say, ‘the greatest danger to which these rangers of the sea seem liable, are, from the mortal hurts that they receive, upon taking on themselves the form of the larger seals or Haaf-fish.’

Hibbert appears to talk with some authority when he explains that the supernatural inhabitants of the sea could take on the form of the fish or the seal on a whim. The idea that the Seal-Folk, just like the fairies or trows, were fallen angels who splashed into the sea, rather than landing on terra firma, was repeated by the Shetland story-teller Brucie Henderson in 1955 (Tocher 8 1972:257):

They say the way at the seals is ill-sanctified is to be the wey at they cam to be i to the sea...God Almighty gives the orders at the Son o the Moarnin and his angels at was been along wi him was supposed to be cast oot o Heaven...the ones at fell on the ground was supposed to be the trows or ferries, and the ones at fell into the sea was supposed to be the seals. And that’s the way at when you see a seal sweemin wi a fine day, if you just look carelessly at’m, at you would think it was a man.

The Seal-Folk were clearly regarded as the sea equivalent of the land trows.

Seal Folk can slough their skins and go ashore where they appear human in appearance. A very common story is that of the Seal maiden - a human male steals the skin of a seal maiden while she is cavorting naked on the beach. The seal maiden has to follow the thief to try and retrieve her skin. Unable to return to the sea without it, she becomes the thief’s wife and bears him children. Years later, she finds her skin and heads back to the sea to her seal lover, whom of course she much prefers.

The same story is told in Ireland, although primarily of mermaids. The story goes that a man catches sight of a beautiful woman on a rock. He seizes her cloak, which she has lain aside to bask in the sun. Having seized her cloak, she is in his power. She returns home with him and has his children. Her husband keeps the cloak hidden, but one day she finds it and is able to return to the sea. Professor O hOgain (Myth, Legend and Romance 1991:187) suggests that this tale springs from an ancient Irish version of the topos of the swan or heavenly maidens, wherea man marries a spirit woman, who leaves him when a ritual taboo is broken. He suggests that it was in Ireland that a version developed where the lady took the form of a seal rather than a mermaid. This version then spread to Scotland and Iceland in the Middle Ages.

There are many versions of the Seal maiden tale told along the Atlantic coasts from Ireland to Iceland. The most famous version in the Northern Isles is probably the Good Man of Wastness from Orkney, while in the Hebrides it would be the story of Clann ‘ic Codrum nan ròn ‘the Clan MacCodrum of the seals’. There is version of the story from the Faroe Islands, about Kopakona ‘Seal woman’, which is set on the island of Kalsoy and there’s another version from Myrdal in the south of Iceland.

The Norwegian folklorist Reidar Christiansen gave this tale the number ML4080 in his list of Migratory Tales. However, as there has only ever been one version recorded from Norway, it is unlikely that the story originated there. O hOgain may be correct that its origins lie in Medieval Ireland. John MacInnes (Dualchas nan Gaidheal 2006:468) agreed that it is in origin a Gaelic tale.

However, I would suggest, that although the original tale of a sea maiden tricked into marrying a man, may well have developed from an ancient Gaelic story, her transformation into a seal maiden is more likely to have happened in the Northern Isles, whence it retraced its voyage south and headed off west. Because although John MacInnes mentions a tale of a seal man from Uist, this seems to be an isolated occurrence, it is in the Northern Isles that we have a range of tales about the interaction of people, both male and female, with seals. For example from Orkney there is the famous Ballad of the Great Silkie of Sule Skerry (Child Ballad 113), which is based on the love between a girl and a seal-man, and from Shetland, from Breckon in Yell, there is the story of the boy with a seal’s head born to an unfortunate woman who fell asleep on the beach. According to Alan Bruford stories about affairs between seal-men and human women are unique to the Northern Isles. There is clearly an uncanny aura about the seals in the Northern Isles.

In a speculative mood, one could ask, if it’s in the Northern Isles that the identification of the seals with marine supernatural beings took place, what is the origin of this belief? If it’s not in the Gaelic west or the Norse east, could it have been amongst the pre-Norse inhabitants of the Northern Isles? Is this a piece of illusive Pictish heritage? I’ll leave that one hanging!

- Finns and the Sea

When it comes to the folklore of the sea, despite being so similar, there is one major difference between the Northern and the Western Isles. In the Northern Isles, the Finns have merged with the supernatural beings of the sea, just as they did with the trows on land. The Finn’s magical aura, his shape-changing abilities and his connection with sea-creatures, such as Fiðr, king of the Finns, turning himself into a walrus, all made the transition possible.

In the Shetlandic tales, the Finns have clearly coalesced with the Seal-folk. A good example from Shetland of a story where Finns and seals are combined is that of Herman Perk and the Sealfrom John Nicolson’s book of 1920 (Some Folktales and Legends of Shetland):

It was believed at one time that the Finns frequently came over to Shetland taking the form of seals. In this connection a remarkable tale was told in Papa Stoor.

The islanders were often in the habit of visiting the outlying Vee Skerries for the purpose of hunting seals. On one occasion a man named Herman Perk, accompanied by others, left for the skerries in a small boat. When they arrived there Herman was landed on the rocks, but his companions remained in the boat to prevent it getting damaged. It happened, however, that a severe storm burst without warning, and the men found after several daring attempts, that it was quite impossible to get Herman off again. The storm was increasing in severity, and latterly they were compelled, for their own safety, to attempt getting back to Papa. After a terrible passage they succeeded in reaching the island, and their first act was to proceed to the home of their ill-fated companion to tell his folk what had befallen him. Imagine their surprise, however, on finding him comfortably seated at his fireside.

Herman had a strange story to tell them. Shortly after the boat left the skerries, he observed a large seal coming up, and as he watched its progress, it suddenly raised itself in the angry sea, and he became aware that it was speaking to him.

"Herman Perk," it said, "you have destroyed many of our folks in your time, yet nevertheless if you will undertake to do me a service, I will carry you in safety to Papa tonight. Some time ago my wife Maryara was made captive in Papa. Her skin is now hanging in the skio (hut for drying fish) at Nortoos, and without it she cannot return with me to Finnmark [in northern Norway]. It is the third skin from the door, and I wish you to bring it to me."

Herman had readily agreed to this proposition, whereupon he was told to cut two slits in the seal's back as supports for his feet, and then place his arms firmly round the animal's neck. The latter immediately took to the water, and in a remarkably short time Herman had the gratification of landing safely in Papa.

True to his promise, he went to the skio indicated, where he found the skin without any difficulty, and carried it down to the beach. The seal was waiting his coming, and at its side was the most beautiful woman he had ever beheld. The seal gave the skin to its lovely companion, and then apparently left its own body behind, and the happy pair immediately took their departure over the sea.

The following morning Herman went again to Nortoos. There, sure enough, lay the skin of a large seal, and it had two cuts behind the flippers. He placed it where he had taken the other from.

After that Herman was a prosperous man, but he was never known to visit the Vee Skerries again. (J.Nicolson 1920:62-63)

A late variant of this story was told to Alan Bruford in Fetlar as late as 1970. An earlier variant was told by Samuel Hibbert, over a century earlier in 1821. In Hibbert’s version the sexes have been reversed and the seals’ names are given as Ollavitinus the son, and Gioga the mother seal, which is the same name as that of the widow Finn in the Foula Finn folk tale, with which I began this lecture.

In Orkney the tradition is a little different. Traill Dennison associated the Finns, or as the Orcadians called them the Fin-folk, with mermen and mermaids, and not with the Seal-folk. However, as has been said and giving precedence to Samuel Hibbert, in essence there was no real difference between these two tribes of the denizens of the deep. The name of the Finns has been changed to Fin Folk (with one /n/), because according to Traill Dennison’s informant, ‘they wear fins; onybody mae ken that’ and they were supposed to don sea-skins, rather than seal skins. It looks as if Orkney originally had the same tradition as Shetland, namely that the Finns had coalesced with the Seal-folk. However, because in Orkney Seal-folk and Merfolk came to be seen as different beings, the tradition underwent further development. Perhaps memories of the magic working Sámi were less imminent in Orkney.

Traill Dennison is the source for most of the Orcadian information on the Fin Folk and it’s clear that he romanticised and systematised his material to a quite a degree. He wrote the material up, turning into readable prose. However, there is no reason to doubt that he has also provided us with some authentic traditions and that he got these, as he always claimed, directly from the Orkney peasantry, such as the old withered woman whom he remembered, with her grey hair and wizened face, who, while darning a stocking, ‘was painting in the most glowing colours, to a group of youngsters, the unequalled charms of the mermaid’ .

According to Traill Dennison, the Fin Folk lived in Finfolkaheem ‘Fin Folk Home’ at the bottom of the Sea, rather than Finnmark in Norway. This name seems to pre-date the loss of the Scandinavian language of Orkney, because it retains the genitive /a/. In the summer they occasionally dwell in the hidden island of Hildaland, which seems to be the same as the Norwegian Huldreland ‘Fairyland’.

The females of the Fin Folk had a hard life. They start off as beautiful mermaids. Then once they married a Fin Man they begin to progressively lose their beauty. According to Dennison:

During the first seven years of married life she gradually lost her exquisite loveliness; during the second seven years she was no fairer than women on earth; and in the third seven years of married life the mermaid became ugly and repulsive. The only way by which the mermaid could escape this loss of her charms was by marrying a man of the human race. And this union could only be consummated by sexual intercourse(Dennison 1995:38-39)

If a Fin Wife had failed to have sex with a human man and had become old and ugly, she was sent on to the land to collect ‘white metal’, that is the old Sámi or Finn favourite silver, for her husband the Fin Man. She earned this money by practising magic and by curing diseases in men and cattle. She had become a witch, a return to the traditional Norse beliefs about the Finns as magicians and magic workers par excellence.

The link with the folklore of witches is maintained by the idea that she also kept a black cat. This feline could turn into a fish to take messages back to Finfolkaheem. If the supply of ‘white metal’ was not up to scratch, the unfortunate Fin Wife could expect a visit from her Fin Man husband, who, upon his arrival, would give her a sound beating which usually resulted in her being confined to bed for days.

The wife-beating Fin Man is not ugly like his Fin Wife, rather he is described as being well-formed, but having a dark, gloomy visage. He also, like the mermaid and his alter-ego the Seal Man, liked to have sexual relations with humans. Again according to Traill Dennision:

Not only did females of the finfolk sometimes become the temporary wives of men, but males of the watery race frequently formed illicit connection with fair ladies on land. These gentlemen never abode for any length of time on shore. They only came on land to indulge unlawful love. And as when divested of their sea skins they were handsome in form and attractive in manners, they often made havoc among thoughtless girls, and sometimes intruded into the sanctity of married life.

Many wild tales were told of the amorous connection between fair women of earth and those amphibious gentlemen. If a young and fair girl was lost at sea, she was not drowned, but taken captive by selkie folk or finfolk. And in olden times mothers used to sin, that is, to paint the sign of the cross on the breasts of their fair daughters before going by sea to the Lammas Fair.

The Orcadian Fin Man has travelled some distance from the Sámi shaman.

Here’s an excellent example of the powers attributed to the Fin Wife. This is the story of the Goodman of Feracleat, Rousay realted by Traill Dennison:

The goodman of Feracleat, in Rousay, was a great trader to Norway. He was sailing home from his third voyage one year, late in autumn, when, overtaken by a violent storm, his boat was driven on shore in Shetland, and he and his crew with difficulty saved their lives. Winter set in rough, and there was no hope of getting to Orkney till spring; so the goodman of Feracleat took lodgings with a canty old wife, who treated him well. Now it happened on Christmas Eve, at supper-time, that the goodman of Feracleat was very dull and downhearted; he ate little and said nothing. The old wife rallied him on his gloomy mood, and urged him to eat; but to little purpose. At length, he began to bemoan himself to her: “Alack-a-day! How can I be merry this night? The morn is Yuleday. Oh , dear! It will be the first Yuleday that I have been away from my ain fireside, and from my wife and bairns since I married. Alas! Well may I be sad and dour!”

“Well,” says the wife, “I warrant ye would fain be aside your ain folk at sic a time. And I’m well sure ye would give the best cow in your byre if ye could be aside your wife by cock-craw on Yule morning.” “Ay, that I would with all my heart, Lord knows,” said he. “Well, well! It’s all well that ends well,” said the wife. “But take ye a drop of gin, and go to bed, goodman; and , if ye tell me your dreams in the morning, I’ll give you a silver merk for Hansel on Yuleday,” so the man went to bed, and never awoke till morning.

The goodwife of Feracleat lay that night lonely and sad; for she did not know whether her husband was dead or alive. And she thought, as she went to bed, it would be a dreary Yule to her. On Christmas morning, when she awoke, she was aware of some one lying under the blankets beside her. And she knew by his deep snoring, that a man lay at her side. She struck at the intruder, crying out: “Ye ill-bred, ill-descended villain! How dare ye come into an honest woman’s bed. Get out, ye muckle beast, or, by the Lord that made thee, I’ll tear thee tae clouts!” “Is that thy voice, my ain Maggie,” said the man, as she attempted to seize him by the throat. When she heard his voice, she cried out, “Bless me! Art thou my own goodman?” And sure enough, so it was. And he had been transported from Shetland to his home in Rousay by the power of the woman with whom he lodged, for she was a Fin Wife witch.

And as the goodwife of Fercleat was rejoicing over her husband’s homecoming, he said, “Goodwife, I doubt thou wilt not be so blithe when thou comes to know what it cost to bring me home!” And they both went into the byre, and found their best cow gone. And the goodwife cried, “Oh, it’s Brenda! She’s taen the best cow, and the best milker in the byre!”(Dennison 1995:36-37)

Some Final Thoughts

Both Spence and Saxby were of the opinion, also expressed by later writers, that the occurrence of the Finns in folklore was due to their actual presence in the Northern Isles. However, there is no need for the Finns ever to have been physically present. Stories and ideas about the Sámi or Finns would have been one of the elements of the intangible cultural heritage brought over by the Norse settlers from Norway. It would have been maintained by continued contact with Scandinavia, particularly in Shetland with its stronger links to Norway over a longer period. Of course, one cannot rule out the possibility that one or two Sámi individuals might have been amongst these early settlers, as has been suggested for Iceland. However, there would not have been many, if any at all. The Finns primarily came to the Northern Isles as folklore beings in the minds of the Norse. This is part of the answer to the question I asked at beginning, ‘who were those poor Finns who were sorely put upon by the Foula men?’ They are a coalescence of the Norse traditions about the Sámi, with their shape-shifting abilities and their maritime connotations, with the supernatural beings of the sea, in particular the Selkies.

Despite the unlikelihood of a physical presence of the Sámi in the Northern Isles, by extraordinary coincidence, during the late 17th century, men were seen off the coast, who appeared to be the mythic Finns or Fin Men come to life. Perhaps due to climatic change in the Little Ice Age, or more likely due to the escape of captured trophies, Inuit hunters were seen in the seas off Orkney. Although the Inuit and the Sámi are completely different ethnic groups, these men in seal skins, rowing swiftly in skin boats, were easily confused with the magical Finns, who by this time must themselves have been confused with the supernatural inhabitants of the sea.

The earliest report of these men is given by the Rev James Wallace in hisDescription of the Isles of Orkney of 1693:

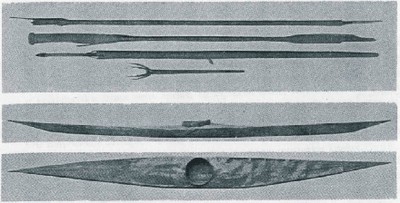

Sometime about this country are seen those Men which are called “Finmen”; In the year 1682 one was seen some time sailing, sometime rowing up and down in his little Boat at the south end of the isle of Eda, most of the people of the Isle flocked to see him, and when they adventured to put out a boat with men to see if they could apprehend him, he presently sped away most swiftly: and in the year 1684, another was seen from Westra, and for a while after they got a few or no fishes: for they have this Remark here, that these “Finmen” drive away the fishes from the place to which they come...These Finnmen seem to be some of these people that dwell about the Fretum Davis, a full account of whom may be seen in the natural and moral History of the Antilles, Chap. 18. One of their Boats sent from Orkney to Edinburgh is to be seen in the Physicians hall with the Oar and the Dart he makes use of for killing Fish.

The Reverend Brand provided some further information:

There are frequently Finmen seen here upon the coasts, as one about a year ago on Stronsa, and another within these few months on Westra, a gentleman with many others in the isle looking on him nigh to the shore, but when any endeavour to apprehend them, they flee away most swiftly; which is very strange, that one man, sitting in his little boat, should come some hundred of leagues from their own coasts, as they reckon Finland to be from Orkney; it may be thought wonderful how they live all that time, and are able to keep the sea so long. His boat is made of seal skins or some kind of leather, he also hath a coat of leather upon him, and he sitteth in the middle of his boat, with a little oar in his hand, fishing with his lines: and when in a storm he sees the high surge of a wave approaching, he hath a way of sinking his boat, till the wave pass over, least thereby he should be overturned. The fishers here observe that these Finmen or Finland-men by their coming drive away the fishes from the coasts. One of their boats is kept as a rarity in the Physicians Hall in Edinburgh.(Brand 1701)

Marischal College, Aberdeen also has one of these boats. About 1700, a man and his kayak were captured at sea not far from Aberdeen; unfortunately he died soon after. The first record of this kayak is in a diary written by a Rev. Francis Gastrell of Stratford-upon-Avon who visited Aberdeen in 1760. He says that,

In the Church which is not used (there being a kirk for their way of worship) was a Canoo about seven yards long by two feet wide which about thirty two years since was driven into the Don with a man in it who was all over hairy and spoke a language which no person there could interpret. He lived but three days, tho’ all possible care was taken to recover him.

Although climatic explanations have been proffered, the most likely reason for the appearance of these Fin Men was the practice of kidnapping Inuit and bringing them back as curiosities to Europe. The Dutch Staten Generaal was so concerned about the extent of the abductions of Inuit that they passed a law in 1720 prohibiting their murder or kidnap (Idiens 1999:163). It is likely that on occasion these captives escaped.

Finally, here is an example of one of these terrible events – the kidnap and transportation of Inuit to present as curiosities to the King of Denmark in 1654:

As soon as this ship appear’d upon the coasts of Greenland, the Inhabitants set out above a hundred boats, and came to view that strange structure, which was much different from what they ordinarily saw. At first they would by no means come near it, but seeing they were entreated to come into the ship, they at last came, and in a few days were so familiar, that with their commodities, which they truckt for such toies as we had, they brought also their Wives, out of an intention to make advantage of them by another kind of Commerce, which though it be not known less elsewhere, yet is not so publickly practis’d Among them, where fornication is neither crime nor sin. The Danes thought this freedom of the Groenlanders a good opportunity to carry away some of them. The Ship being ready to set sail for its return, and the Savages coming still aboard with their Commodities, a Woman that had a great mind to a pair of knives which one of the Sea-men wore at his Girdle, offer’d him for it a Sea-Dogs skin, which the Sea-man refusing as too little, she proffer’d him a kindness into the bargain. The Sea-man had no sooner express’d his being well satisfy’d with the proffer, but she begins to untie the point (for they as well as the men wear Drawers), and would have laid herself down upon the Deck. But the Sea-man made her apprehend that he would not have all see what they did, and that she must go under Deck. The Woman, having got her Father’s leave, followed the Sea-man with two other aged women, a young Boy, and a Girl about 12 years of age, who were to be present at the consummation of the bargain. But as soon as they were down, the hatch was shut, they laid hold also of another Man, and set sail (Olearius 1656).